Pacing

People living with persistent pain find that pacing is one of the key everyday skills to learn and use.

Pacing can help you achieve your goals without increasing your pain or letting tiredness force you to stop.

As you’ll see, pacing is like the story of the tortoise and hare: slow and steady wins the race . . .

How can pacing help in managing persistent pain?

Pacing means changing how you exercise and do daily activities so as not to flare-up your pain and to gradually increase what you are able to do.

Pacing helps you to become more active and fitter, stronger and healthier.

Pacing is about choosing when to take a break from an activity – before pain, tiredness or other symptoms become too much. In other words, not carrying on until pain forces you to stop.

Here are some of the positive changes that people with pain noticed after they learnt the skills of pacing:

Positive changes reported by people who learnt to pace

Doing more

They could achieve their goals – and tick more things off their ‘to-do’ list.

Sleeping better

They could sleep better at night.

More control

They felt they had more control over the pain and their activity levels.

Less medication

They depended less on medications and thus experienced fewer unpleasant side effects.

Brighter moods

Life became more enjoyable – they had more fun.

More energy

They felt stronger and more energetic – they had more ‘get up and go’.

A better social life

With more confidence that their pain was manageable, they could plan for a better social life and do more things with family and friends.

Less pain

They found they had less pain and had fewer setbacks. If they did have setbacks, they didn’t last as long.

Less effort

They felt less effort was required to achieve daily tasks and activities.

Good pacing or bad pacing?

Whether we know it or not, we all do some kind of pacing – it just might not be the best kind for us.

Generally speaking, there are three unhelpful styles that people with persistent pain often use

- overactive

- underactive

- ‘boom and bust’

As you read about unhelpful pacing styles below, decide which pacing style you currently use.

Overactive pacing

This means doing too much activity or too many tasks over a short space of time.

Typically, this happens if you are having a good day, with less pain, or your mood is better: you try to do too much and end up with more pain and tiredness. This means you miss out on enjoyable things because you have to take time out to recover.

Underactive pacing

Underactive pacing means that you are doing too little activity to help keep up your strength, stamina and flexibility in your muscles, ligaments, joints and bones.

Most of your time is spent resting, sitting or lying down, which is understandable, especially as lack of fitness makes muscles and other tissues tight, weak and painful.

However, this can actually add to your pain, so over time you end up doing less and less because of the pain.

‘Boom and bust’ pacing

Often people use pain and energy levels as a guide to their activities and pacing them. This means they risk doing too much activity on good days (overactive), which makes their pain worse. They are then forced to rest while the pain settles down (underactive).

This is a mixed style of pacing, which is unhelpful in the long term. It’s sometimes known as ‘boom and bust’.

Tools and resources to help you pace well

Whether you feel that you tend towards being an overactive pacer, an underactive pacer, or a ‘boom and bust’ type of pacer, then the good news is there’s lots you can do to change your pacing style. Here are four suggestions for you to try:

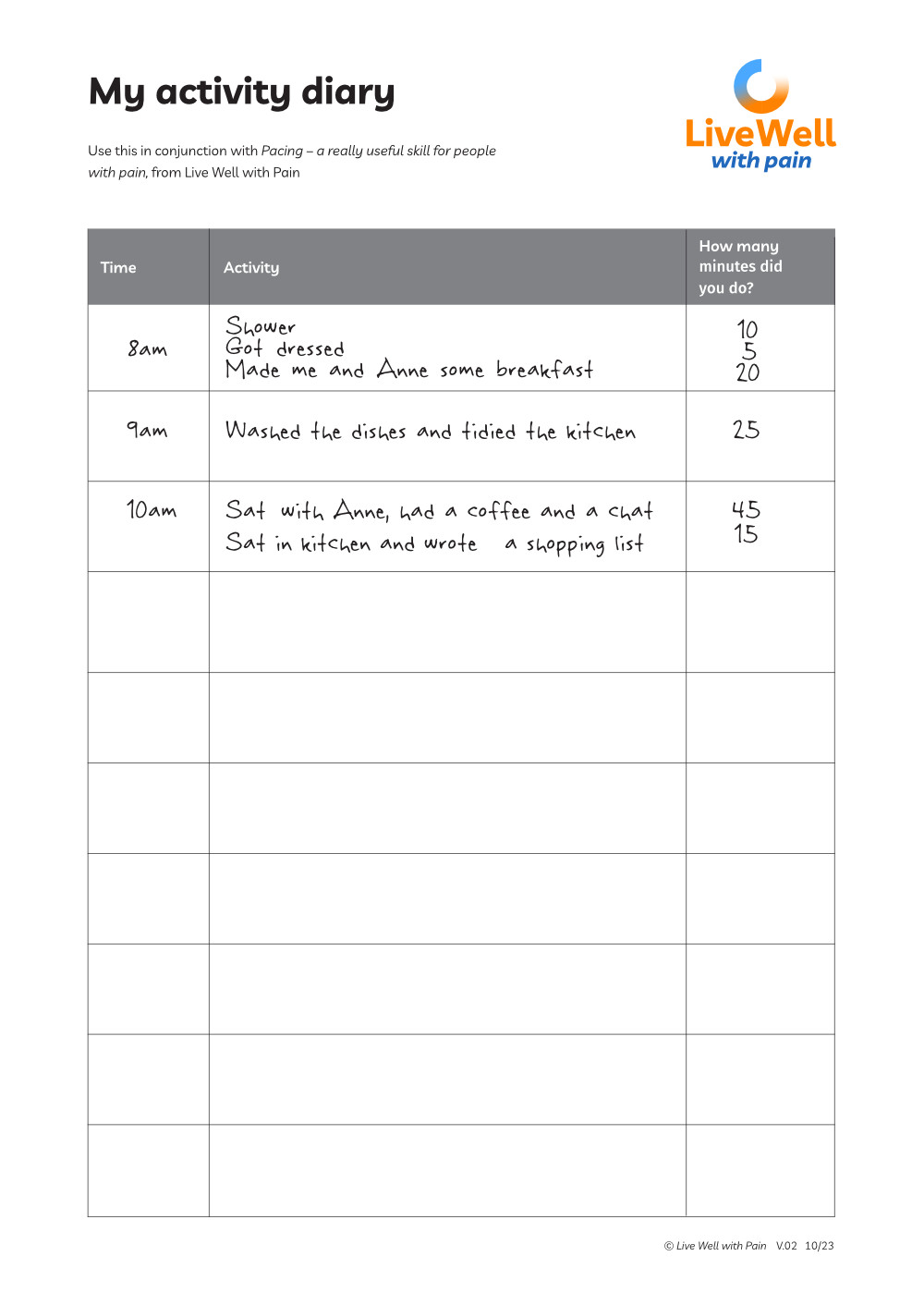

My Activity Diary

To learn how to pace well, it’s important to understand what your pacing style is now. A good way to do this is to track your activities with an Activity Diary.

How to do it

Fill in the Activity Diary for at least two days. To do this you will need to:

- shade in the boxes for the hours when you were asleep

- fill in what you were doing and for how many minutes each time

- write down when you took a break, sat down or lay down, and for how long

What to do next

When you have completed your Activity Diary, what do you notice about your pacing style? Use these questions to guide your thinking and write down your answers:

- How much activity did you do each day? (in hours or minutes)

- How much time did you spend resting, sitting or lying down each day? (in hours or minutes)

- How many hours were you asleep each day? (in hours or minutes)

- Did you manage to do the things you needed to do?

- If yes which ones?

- How much effort did your activities take on a scale of 0 to 10?

Do you think your current pacing style is mainly underactive, or overactive, or a mixture of both styles?

You can downlaod this PDF resource and print it out:

Use an Effort Scale

An effort scale is a good way to check whether an activity you are planning to do is likely to be:

- too much effort (leading to overactive pacing)

- too little effort (underactive pacing)

- or just right

Learn how to use an effort scale for pacing

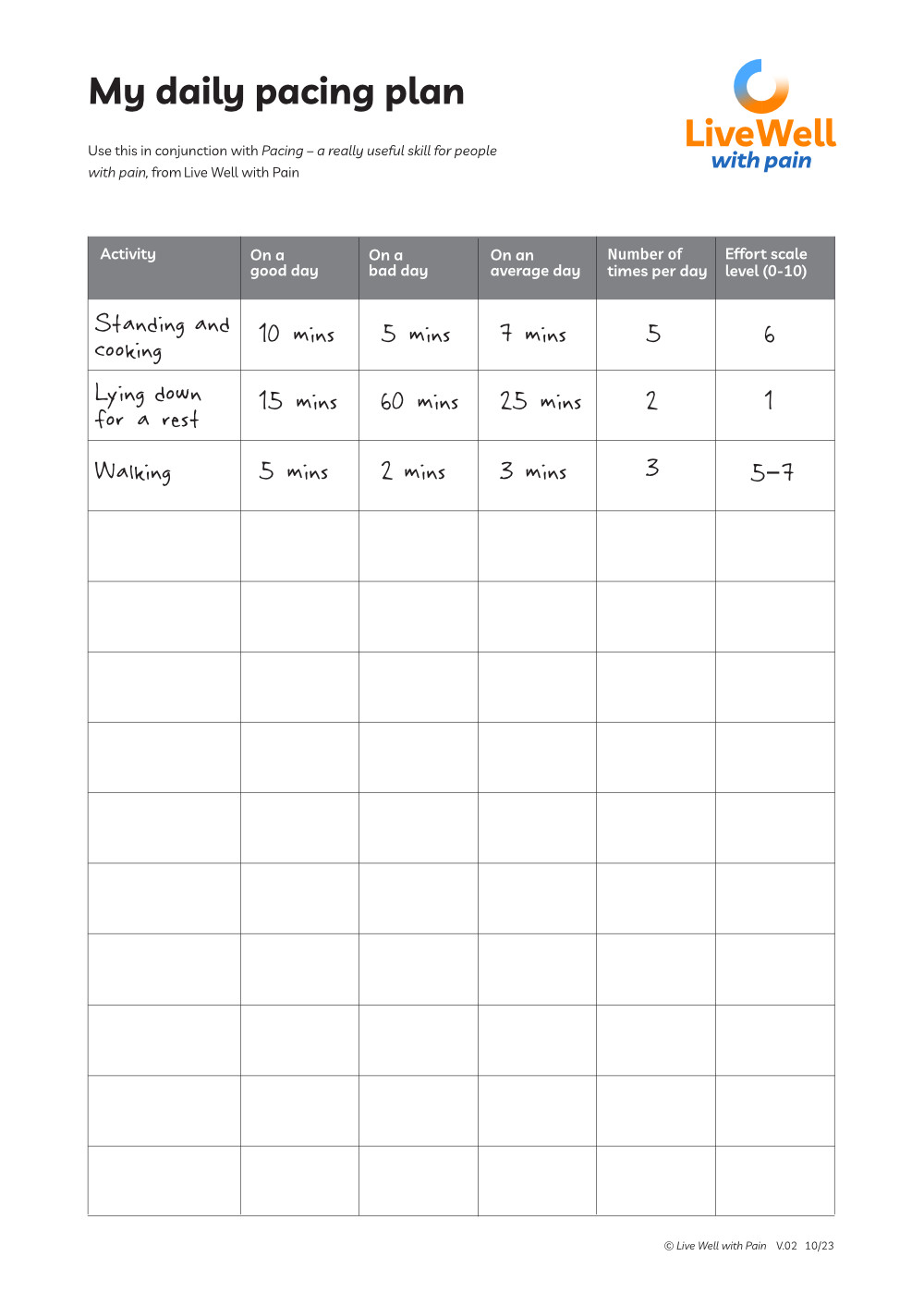

My Daily Pacing Plan

Try creating a Daily Pacing Plan to help you balance and pace your activities.

Balancing the body and mind together on activities helps do what you want to do. This will help control your pain and life with more success and less stress and move on in your life journey.

Give pacing a go and start with a pacing plan and reward yourself for achieving a helpful habit for life.

Here are some ABC questions to help you build your Daily Pacing Plan:

A: What Activities can I pace today?

B: How long before I take a Break?

C: Check what is the effort level on an Effort Scale

You can find out more about using an Effort Scale in Footstep 3 – Pacing.

You can downlaod this PDF resource and print it out:

Balanced thinking

Helpful pacing also needs balanced thinking that helps you to balance the time spent on an activity with rest periods or breaks.

This thinking helps you keep up the activities which you value and are part of the goals that you want to achieve. It is a really tricky skill to learn and use, yet makes a positive difference to being more active, to your sleep and even to the pain itself.

To help develp balanced thinking, try to be aware of:

1. Thoughts like ‘must’ or ‘should’

Replace these with ‘could’. For example, instead of thinking ‘I must get it all done today’, try kinder thoughts such as: ‘I could choose to pace, and do it in stages over two or more days.’

2. Thinking that all the jobs must get done today

Watch for the unrealistic ‘all or nothing’ thinking styles as they are rarely helpful. It is not giving in to do it in a paced way!

True story

“I’d always pushed myself harder or longer to get things done”

Before developing neck pain, Arvind had always overdone things. Now that was no longer an option, Arvind had to find another way. He needed learn pacing or he was in danger of letting people down. Which is something Arvind couldn’t stand . . .

Read more

Useful resources

Pacing

Many people living with pain go through the ‘boom and bust’ cycle. This means they do too much activity on good days (boom). That makes their pain worse. They are then forced to do nothing (bust) while the pain settles down again.

This leaflet will show you how to balance activities throughout the day so that you can avoid the ‘boom and bust’ cycle.

Using the techniques in this leaflet, over time you will be able to achieve more, with fewer setbacks.

Pacing

Key ideas

✔ Pacing is one of the key self management skills for people living with persistent pain

✔ It can help you achieve your goals without increasing your pain

✔ There are both helpful and unhelpful styles of pacing

✔ Changing your pacing style could bring many benefits and lessen your pain