Medicines and nutrition

We now know that pain medicines only reduce pain for about 40 percent of people who use them. They appear to become less effective the longer people remain taking them. Side effects of pain medicines can have a major impact on a person’s life.

Side effects such as sedation, fatigue and weight gain can make it harder for people to become more active, something we are confident has a positive effect on pain and well-being. At least 50% of people with pain are overweight and pain medicines can make that harder to change.

So supporting a person with pain often involves making changes with both medicines and nutrition . . .

For a lot of people living with pain, medicines are a mainstay of their pain management. Whilst we often call these medicines ‘painkillers’ this is not, for many people, an accurate term. So exploring whether medicines are really helping someone can be an effective way of encouraging them to consider other ways of living well with their pain.

You role is to guide the person in the safe and effective use of pain medicines, ensuring they do not inadvertently come to harm.

You can do this by:

-

Finding out whether the pain medicines are actually helping the person to do more in their lives, and similarly, what they still find difficult in spite of the medicines.

-

Helping the person to understand the risks and potential long-term harms of pain medicines, and exploring how these might be affecting them.

-

Ensuring you have introduced other concepts of supported self management such as pacing and goal setting.

1. Medicines

Learning about pain medicines

What’s wrong with the term ‘painkillers’?

Most people (and many clinicians) will refer to pain medicines as ‘painkillers’. It’s a term that implies taking them will result in pain going away completely.

Unfortunately, for the majority of people who are prescribed pain medicines or who buy them over-the-counter, that will not be the case. However, the term ‘painkiller’ can, unhelpfully, lead people to conclude that the reason their pain has not yet gone, is because they have not yet taken enough or have not yet had the ‘right’ medicine.

Simply, only about 40% of people prescribed analgesics (including gabapentinoids and antidepressants) will gain meaningful benefit from them. What is meant by benefit is at best, a 50% reduction in pain intensity.

For opioid medicines e.g., codeine, tramadol or morphine, it is likely to be only 10% of people gaining benefit.

Yet most people receiving these medicines are unlikely to be aware they might not ‘work’. This can result in people seeking higher doses or alternative drugs when, what they are prescribed does not give them the outcome they were hoping for.

Are all people using long-term analgesics addicted?

In short, no – most people using pain-relieving medicines prescribed by health care professionals are unlikely to be ‘addicted’ or displaying signs of misuse.

However, lots of people, especially when medicines have been used for a period of time, will have a physical dependence. This can be observed if the medicine is suddenly stopped, or a dose is missed for example. People experiencing withdrawal might mistake it for evidence of addiction. Health care practitioners’ can also mistakenly diagnose ‘addiction’ when a person has actually experienced withdrawal.

Changing the conversation

It is not a person’s fault that they often want more or different pain-relieving medicines when they are not likely to be aware that they do not ‘work’ for everyone.

It is important to have honest and open discussions with people about their medicines, whether that is at the start of treatment or when reviewing and discussing if they should continue.

It is never too late to introduce this information, but we should be mindful that people who have taken pain medicines for long periods of time, may feel confused that they are only just being told.

For the majority of people, despite publicity about the risks of analgesic medicines, being told that ‘painkillers do not kill pain’ challenges their beliefs and so it is important to give people time to process and make sense of the information.

Why should pain-relieving medicines be used?

The role of any analgesic medicine in pain management, whether paracetamol, gabapentin, anti-depressants or opioids, is to reduce pain intensity AND allow improved or maintained function. In other words, they are used to help the patient do more of the things that matter to them.

If medicines are not allowing them to do more, which may be because they do not reduce pain intensity or may be due to side-effects, then they should be carefully reduced and stopped at a time and pace the person can manage.

Particularly with persistent pain, pain intensity can be hard for the person to gauge – we know pain fluctuates day to day, can flare up and settle down. For this reason, in a clincial context, it can be easier for both the patient and the practitioner, to monitor what the person is doing (function): if someone is doing more, it is very likely the pain is interfering less and therefore, the intensity of pain is also likely to have reduced.

Actions you can take

Starting pain relieving medicines

Whilst most people will not gain much benefit from taking pain-relieving medicines, it is not possible to know who those people are until they have taken them. It is important to understand the evidence that supports the use of analgesic medicines in particular pain conditions. For example, opioids are not recommended for long-term low back pain, as the associated harms are thought to outweigh any likely benefit. It can be easier not to prescribe in the first place, rather than try to stop medicines later on.

If you are planning to start a prescription, explore the resources in our Skills and Knowledge section under Medicines and your patient.

- Familiarise yourself with any local pain management guidelines and formulary options

- When an analgesic is indicated, ensure the patient understands it will be a trial and not an indefinite prescription.

- Agree a goal with the patient which will be used to review whether the pain-relief is helping or not. This could be an improvement in sleep, a short daily walk or something they feel is achievable and meaningful. A goal should be agreed whenever a dose is changed and even if the patient is already taking analgesics. Supporting the patient to develop their goal setting skills (Footstep 4: Setting goals) is important here.

- Agree what dose will be prescribed, if it can be increased and by how much and when.

- Agree when the review will be – normally two weeks after starting the trial in the first instance.

Reviewing pain relieving medicines

Review the outcome of the trial or dose change against the agreed goal that was set.

If the patient is not able to demonstrate progress towards the goal, explore why that might be e.g., pain intensity not reduced, side-effects of the medicine.

If progress is being made, agree the next goal and whether the medication will be maintained at the current dose or changed.

Set the date for the next review – this may be a longer period than the first but should not be greater than 1 month until regular progress is being demonstrated.

If you are planning to review a prescription, explore the resources in our Skills and Knowledge section under Medicines and your patient.

Tapering pain relieving medicines

Health care organisations and practitioners are being encouraged to review analgesic medicines, especially for people who have been using them for extended periods of time or at high doses e.g., greater than 120mg oral morphine equivalent daily dose.

Whilst it is important not to continue medicines that are unhelpful or which are harmful, it can cause patients to feel targeted or that they are having changes made without their agreement.

Patients tend not to know what the side effects of a medicine are, so consider asking them what other issues they have noticed or problems they are experiencing.

These can then be linked back to the medication e.g:

- drowsiness, sedation may be due to opioids, gabapentinoids and antidepressants, worse in combination

- dry mouth can be caused by antidepressants and is also associated with longer-term use of opioids

If you are planning to review a prescription, explore the resources in our Skills and Knowledge section under Medicines and your patient.

More tips for tapering medicines

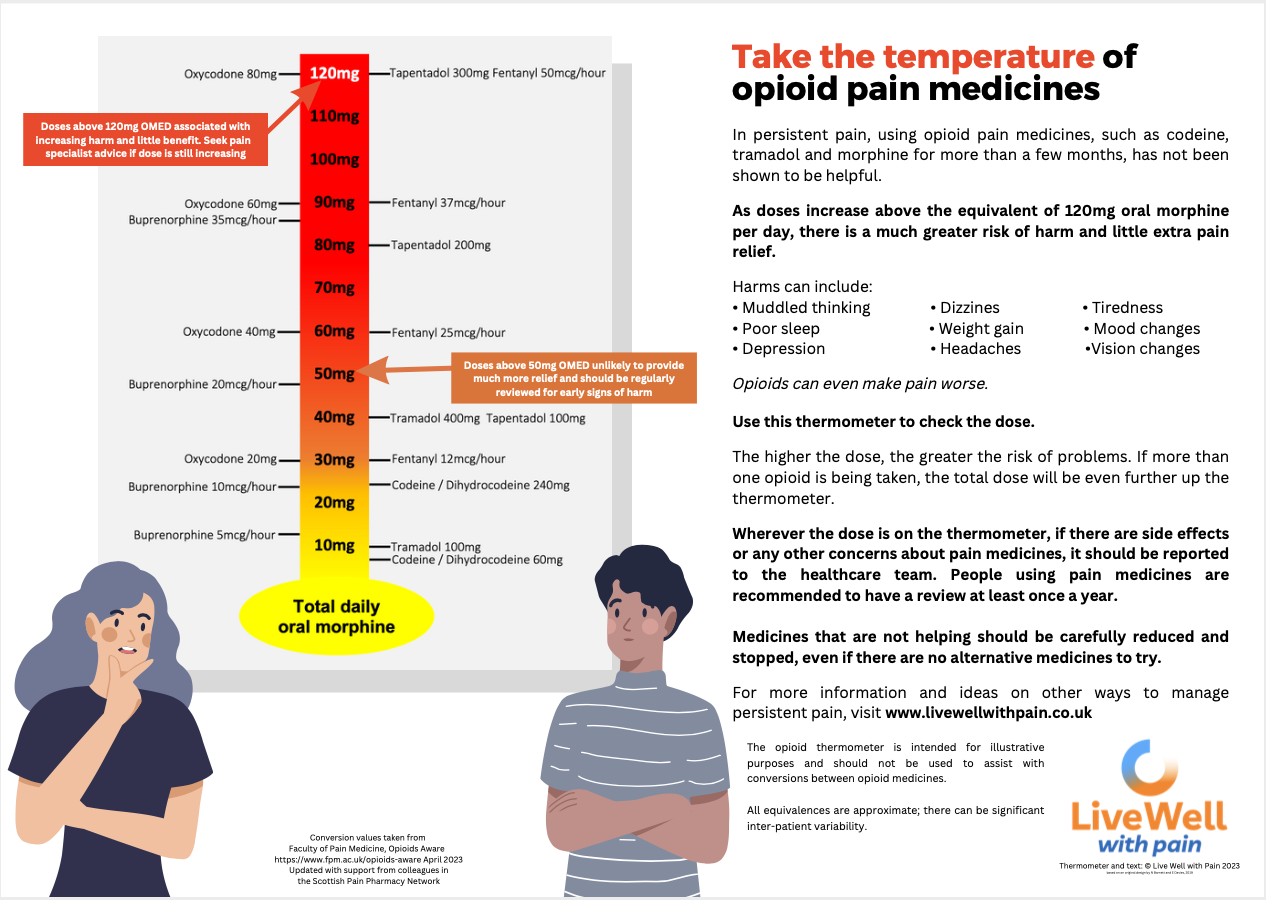

An opioid thermometer

How much opioid is a person taking? The opioid thermometer helps to estimate dosing based on oral morphine equivalent dose, and can be used to guide safer prescribing.

The PDF contains two versions: the first goes up to 120mg morphine per day, the second to 250mg morphine per day.

Medicines resources you can use with the person you are supporting

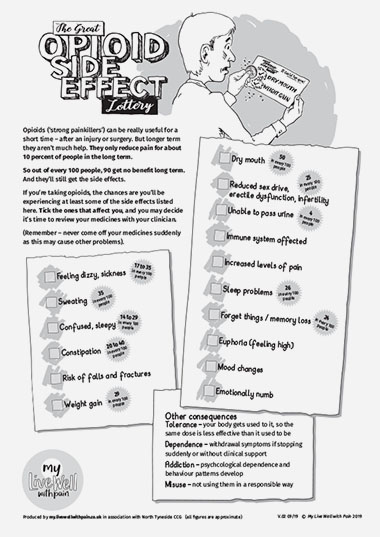

The Great Opioid Side Effect Lottery

Often, patients being prescribed opioids for their persistent pain do not know how little benefit they offer over the long term, or how prevalent and varied are the side effects people experience.

This A4 sheet, designed to be used by clinicians in their consultations with patients, is a simple way to raise the question of benefits versus side effects.

Using a ‘lottery scratch card’ metaphor, the sheet explains that opioids only actually reduce pain for around 10% of people in the long term, and their side effects can be both wide ranging and serious.

It lists many of the side effects, and provides a number of statistics to show how common these side effects are.

Working through the list with your patient, ask them to tick those side effects they are experiencing, as a starting point for introducing the idea of a medicines review.

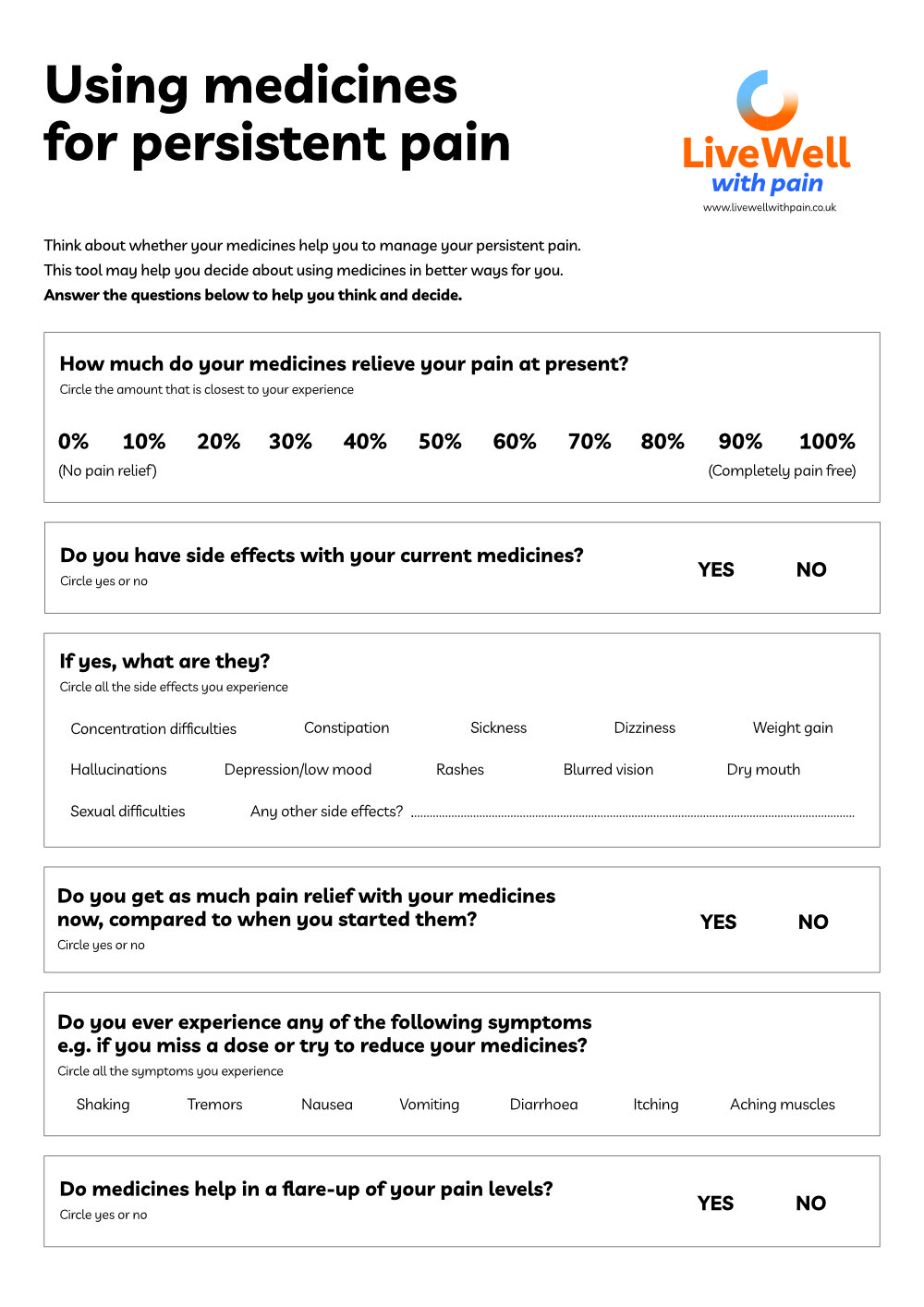

Medicines Decision Guide

Are you wondering whetherthe pain medicines you take are really helping?

Complete this guide and and share it with your GP, pharmacist or pain management team. It will help them understand why you may be thinking about continuing, reducing or stopping your pain medicines.

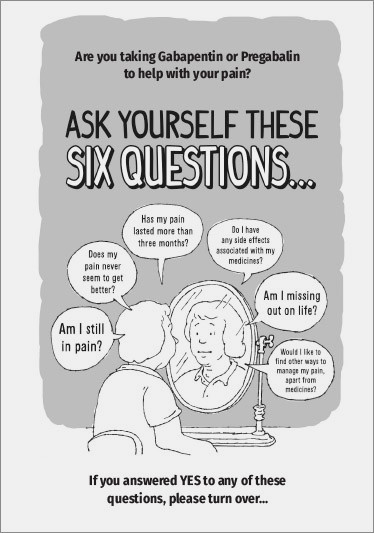

Ask yourself six questions

Designed for patients who have been taking Gabapentin or Pregabalin to help their long term pain for more than three months, this leaflet invites them to consider six key questions. And if their answer to any of them is ‘yes’ the leaflet provides an accessible overview of the main issues and what else, apart from opioids, a person can do to manage their persistent pain.

Painkillers – the downside

Fun poster with a serious message – put it up in your waiting room to raise awareness of the dangers of long term opioids use to control pain. Includes a 'call to action' to talk to the healthcare team about better ways to manage pain.

2. Nutrition

A combination of the side effects of medicines, together with being less active because of the pain, can lead to becoming overweight.

This affects at least 50% of people with pain.

So losing weight is likely to be useful, but ‘diets’ may be psychologically unhelpful – so for more positive outcomes focus on healthy eating with greater levels of activity.

Healthy eating

- Losing weight is likely to be helpful but ‘diets’ may be psychologically unhelpful – focus on healthy eating with greater levels of activity for more positive outcomes

- Focus on high quality nutrition e.g. a Mediterranean type diet as suggested in NHS Eat Well

- Public Health England recommend a vitamin D supplement daily for all and a dose of 10 micrograms/day to limit emergence of osteoporosis, especially in autumn/winter

- If you have access to local weight loss support services, consider referral – this group support may also help with social connectedness

Footstep 9 – Medicines and nutrition

Summary of key points

✔ Pain medicines remain a major part of most people’s pain management, however they are poorly effective for the majority of people

✔ Side-effects of pain medicines, especially opioids and gabapentinoids, can make living with pain much harder but few people are aware of the problem.

✔ It is important to change the conversation about pain medicines, focusing on what they enable the person to do, rather than whether they take pain away

✔ Nutrition is important for a person’s general health and well-being. The focus should not be just on weight loss but supporting someone to make healthier choices, when possible and to see food as part of their management plan